“We have not adequately defended our constitutional republic from within,” writes Thomas Griffith, adding his voice to a growing list of commentators, politicians, and nonprofit leaders who see civics as a cure-all for our political woes. “Our education system has by and large abandoned civics and American history. This failure to teach civic education has contributed to a growing loss of appreciation for democracy.”

Conservative pundits in particular have led the call for national civics reform, specifically citing our great national “failure” or “crisis.” James Stoner and Paul Carrese, writing in defense of the Educating for American Democracy curriculum roadmap, argue their report was a response to our present day crisis. The crisis: “Young Americans’ obvious ignorance of the country’s history and its forms of government, evident in standardized tests and in dozens of more intuitive measures.”

Likewise, Representative Tom Cole (R-Okla.) points to the importance of civic knowledge as the main reason he is cosponsor of the recently introduced Civics Secures Democracy Act. “As a former history teacher,” Cole says in a press release about the bill, “I believe that lack of knowledge of America’s history is one of the greatest threats to preserving our republic and ensuring a prosperous future for generations to come.”

“Action Civics” Over Civic Knowledge

Of course, Cole et al. have a point. Students across the country don’t know our history very well. Many receive no formal education in civics, and it shows. In recent surveys cited in another federal bill, only one-third of Americans could identify all three branches of the federal government, and roughly the same amount failed to name a single right guaranteed by the First Amendment.

The arguments of conservative supporters, however, have set up a dazzling bait-and-switch.

The Civics Secures Democracy Act would give $1 billion over the next five years to nonprofits, for the purpose of “developing or expanding access to evidence-based curricula.” One key evidence-based practice identified in the bill: “service learning and student civic projects linked to classroom learning.” Also known as “action civics,” these projects are now a favored pedagogical tool of civics education nonprofits, which would benefit greatly from a massive influx of cash. Unsurprisingly, the Educating for American Democracy roadmap also touts action civics as a useful tool.

The premise behind action civics is that students learn best by doing—so students should conduct political advocacy projects, rather than staying in the classroom. In other words, they should become activists.

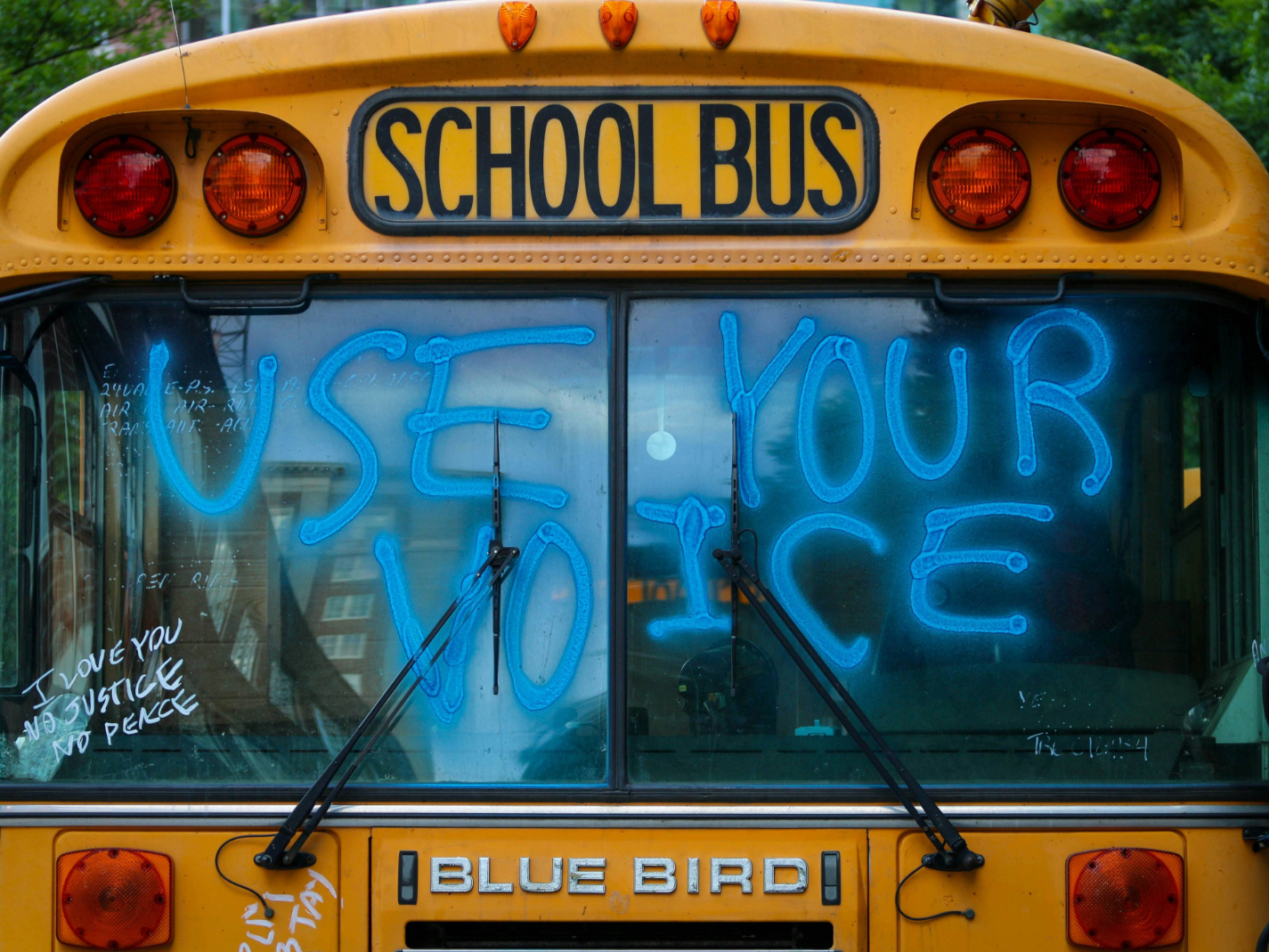

One article championing the model describes the steps students take to complete their projects: “articulate a concise, concrete goal,” “identify the people who have the power” and “the people who could influence those in power,” and finally “build a multi-tactic campaign to achieve their goal.”

If only such “understanding” were a predictable outcome of the bill he sponsors. As it stands, the bill is like trying to improve test scores by mandating free iPhones for every middle schooler.

If this sounds like a way to overtly politicize the classroom, that’s because it is. But there’s a more basic flaw: it doesn’t teach civics in any meaningful sense.

The premise behind action civics is that students learn best by doing—so students should conduct political advocacy projects, rather than staying in the classroom. In other words, they should become activists.

Generation Citizen, a nonprofit that promotes action civics, defends the pedagogy on the grounds of its efficacy. In response to criticism, Amy Curran and Scott Warren, the Oklahoma Executive Director and CEO of Generation Citizen, wrote “we include these elements not because they breed progressivism, but rather because they are based on effective and proven learning approaches that studies show are the most efficient ways to teach civics education, period.”

Generation Citizen has a vested interest in making this point. After all, priority for funding in the Civics Secures Democracy legislation is tied to “evidence-based practices.” While the studies that Curran and Warren reference show that action civics can produce various learning outcomes, those outcomes are—at best—tenuously mentioned to what most people mean by the word “civics.”

According to the studies cited, action civics is designed to produce six outcomes: “21st century positive youth leaders, active and informed citizens, academically successful students, youth civic participation, youth civic creation, and civic and cultural transformation.”

This research lets Generation Citizen declare success without ever addressing the civic knowledge problem, the very problem that every civics bill ostensibly is designed to address. By the very tools used to measure the efficacy of action civics, students need not have knowledge of America’s history, the Constitution, and the inner functioning of government. It is enough for them to demonstrate the skills of “collective efficacy,” “youth efficacy,” “media consumption,” “analyzing power,” and “strategy.”

Worse Than Doing Nothing

The disjunction is clear. Conservative proponents argue that these civics measures are needed because “[w]e have not adequately defended our constitutional republic,” or because of “Young Americans’ obvious ignorance of the country’s history and its forms of government,” or because “lack of knowledge of America’s history is one of the greatest threats to preserving our republic and ensuring a prosperous future for generations to come.” But proponents of action civics never purport to solve this problem. By their own measures of success, students could carry on in blissful ignorance.

Hence the bait-and-switch. While advocates lament our lack of civic knowledge, a key tool they fund would do nothing to address the problem.

It’s damaging enough to displace civics with a photogenic distraction. Civics is important; our horrible record shouldn’t be wished away with a premature “mission accomplished.” But action civics does more than distract—it teaches a warped conception of politics: a technocratic approach to political problems, a conception of civil discourse that reduces political dialogue to protest, a simplistic understanding of political issues, a hardline approach that eschews compromise, an understanding of civic engagement as the mere procurement of state resources, and a self-congratulatory standard of success.

“When Americans have a deeper understanding of our nation’s history and founding principles,” Cole says, “they become more engaged citizens, who participate in our government the way our Founding Fathers intended.”

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by American Greatness on June 18, 2021, and is crossposted here with permission.