The C3 Framework

Introduction

American K-12 Civics education reform must take account of the larger social studies curriculum. Public schools teach civics in coordination with other academic content areas, including history, geography, economics, and other social sciences. Our public schools must teach each of the social sciences properly, as well as the social sciences as a whole, if they are to teach civics education properly.

Unfortunately, most states cannot teach social studies properly because during the last decade they have formally or informally adopted the National Council for the Social Studies’ College, Career, and Civic Life (C3) Framework for Social Studies State Standards.1

The C3 Framework substitutes process for content, yokes social studies instruction to the failed Common Core standards, and politicizes social studies curricula based on those standards. Civics education reformers must be particularly alarmed, however, because the C3 Framework subordinates all of social studies instruction to action civics (also known as “civic engagement” or “protest civics”), which replaces civics education with vocational training for left-wing community organizing.2 We particularly condemn the C3 Framework’s subordination of academic knowledge and social studies to action civics, but each of the C3 Framework’s flaws would be sufficient reason by itself for a state to reject using it to inform its content standards and curricula.

Learning How to Think About Nothing

The C3 Framework provides no content at all, only content-empty “skills” for how to conduct the different forms of social science inquiry—civics, history, economics, geography, psychology, sociology, and anthropology. The C3 Framework argues that “[t]he days are long past when it was sufficient to compel students to memorize other people’s ideas and to hope that they would act on what they had memorized. … Children and adolescents are not empty vessels into which we pour our adult ideas and knowledge”—and so it provides no knowledge at all.3 As Chester E. Finn, Jr. of the Fordham Institute put it,

This framework is avowedly, even proudly, devoid of all content. Nowhere in its 108 pages will you find Abraham Lincoln, the Declaration of Independence, Martin Luther King (or Martin Luther), a map of the United States, or the concept of supply and demand. You won’t find anything that you might think children should actually learn about history, geography, civics, or economics. Instead, you will [find] something called an ‘Inquiry Arc,’ defined as ‘a set of interlocking and mutually supportive ideas that frame the ways students learn social studies content.’4

Chester E. Finn, Jr., “The failure of civics education—and the Brown Center,” Thomas B. Fordham Institute, July 18, 2018.

E. D. Hirsch long since provided a devastating critique of the skills-centric pedagogy that the C3 Framework embraces.5 Students cannot learn process without content, and the more content they learn, the more they are able to process that content. The C3 Framework precisely reverses reality when it argues that “[i]f 20 years of National Assessment of Educational Progress report cards on youth civic, economic, geographical, and historical understanding mean anything, they repeatedly tell us that the success of that telling-and-compelling effort no longer works in the 21st century, if it ever did.”6 The decline of student knowledge tracks with the abandonment of content-rich instruction, a disaster which the C3 Framework now wishes to compound. Moreover, to make process the framework of subject standards and curricula inevitably leads teachers to discard the content, which is optional, for the process, which is not.

The C3 Framework early produces a disingenuous disclaimer:

What Is Not Covered in the C3 Framework … Content Necessary for a Rigorous Social Studies Program. The C3 Framework focuses on the concepts that underlie a rich program of social studies education. The foundational concepts in Dimension 2 outline the scope of the disciplinary knowledge and tools associated with civics, economics, geography, and history. References are made to a range of ideas, such as the U.S. Constitution, economic scarcity, geographical modeling, and chronological sequences. However, the particulars of curriculum and instructional content—such as how a bill becomes a law or the difference between a map and a globe—are important decisions each state needs to make in the development of local social studies standards.7

C3 Framework, p. 14.

This disclaimer obscures how greatly the C3 Framework constrains each state’s ability to provide “the particulars of curriculum and instructional content.” Each state—and, therefore, each teacher—must first provide the instruction in process that the C3 Framework mandates, which limits the amount of content the state can provide. Each state is compelled to provide only content that supports the C3 Framework’s frequently politicized instruction focused on process. Each state, moreover, must accede to the C3 Framework’s presumption that any social studies content can only be justified in the first place by supporting the C3 Framework’s process instruction.

The C3 Framework’s subordination of content to process fundamentally misunderstands the point of school instruction. We do not have schoolchildren read the Declaration of Independence to help them learn source evaluation skills. We teach schoolchildren source evaluation skills so they can appreciate more deeply the Declaration of Independence. The C3 Framework makes it impossible for any state to start with documents and facts that students should know and then adopt whatever pedagogy best forwards instruction in those documents and facts.

No state can adopt the C3 Framework without committing itself to rigid constraints on what facts can be taught. No state can adopt the C3 Framework without committing itself to disdain for the primary importance of teaching and learning factual knowledge. No state can adopt the C3 Framework without regarding the Declaration of Independence as nothing more than an interchangeable prompt for social studies skills.

The Dead Weight of the Common Core

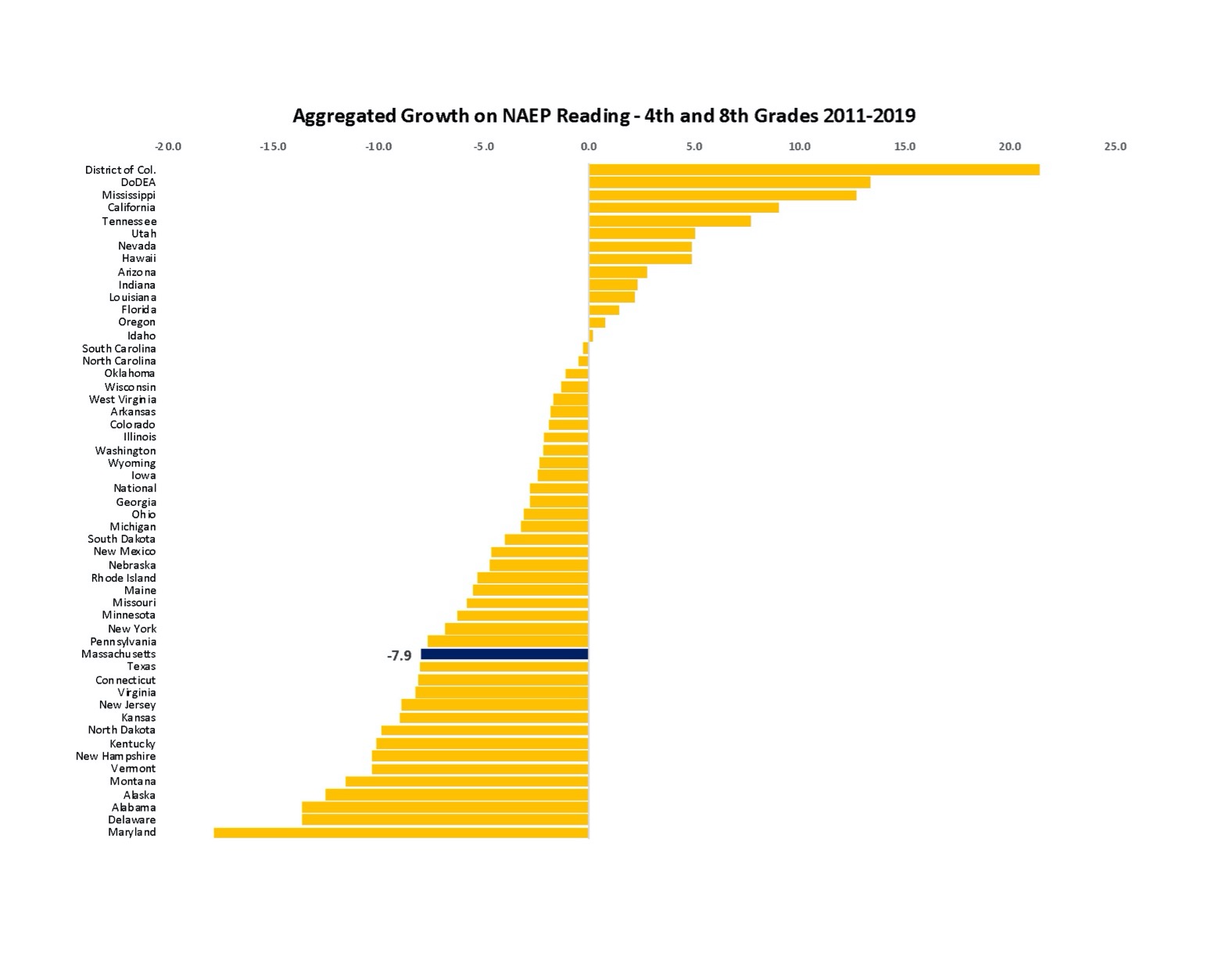

The C3 Framework explicitly links its framework to the Common Core Standards for English Language Arts/Literacy: “The C3 Framework fully incorporates and extends the expectations for literacy learning put forward in the Common Core Standards for ELA/Literacy. … . In places, the connections between Common Core Standards and C3 Framework Indicators are so close that the same language is used.”8 The Common Core standards, however, have failed nationwide. They generally have reduced literacy throughout the fifty states, because the Common Core’s misguided pedagogy is a dead weight on student achievement, not a challenging standard to push students to higher achievement.

Aggregated Growth on NAEP Reading 4th and 8th Grades 2011-2019 9

The Common Core standards, of course, share the C3 Framework’s misguided focus on process rather than content. More precisely, the C3 Framework shares the same process standards as the Common Core. States that adopt the C3 Framework invite a reduction in civic and historical knowledge as damaging as the Common Core’s reduction in student literacy.10

The C3 Framework’s subordination of social studies to literacy, moreover, redoubles the error it commits by subordinating content instruction to process instruction. Let us return to the Declaration: we do not have schoolchildren read the Declaration of Independence to help them learn their letters. We teach schoolchildren their letters so they can read the Declaration of Independence. For all that the C3 Framework claims to instruct students in “disciplinary practices,” it denies the social sciences any genuine autonomy.11 The C3 Framework subordinates civics, history, economics, geography, psychology, and anthropology alike to the need to teach basic literacy and “skills” that are equally appliable to any mode of inquiry. The C3 Framework makes it impossible to teach these disciplines as valuable precisely because their mode of inquiry cannot be transferred to another discipline. The C3 Framework, itself a slave to the Common Core,in turn enslaves these disciplines by rendering as interchangeable any historical fact or document.

Politicized Disciplines

The C3 Framework commits itself to an extraordinarily politicized framework for instruction. Generally, the C3 Framework commits social studies to instruction in “multi-cultural and global understandings, the ability to work with diverse groups,” which euphemizes instruction in the ideologies of “multiculturalism” and “diversity.”12

The C3 Framework forwards this general ideological thrust with the willing collaboration of activists within each of the social science disciplines, who have not needed the prompting of the Common Core and C3 Framework authors to politicize their disciplines. These activists all too frequently have seized control of the professional organizations of their disciplines, but they possess no authority to remake their disciplines. Each state has a responsibility to remove the politicization introduced by radical activist zealots from their own content standards. The C3 Framework, by surrendering the definition of the disciplines to these activist zealots, has produced a framework that prevents actual instruction in the disciplines it purports to teach. No state can use the C3 Framework and provide its schoolchildren an objective, comprehensive, or even professionally adequate introduction to the social science disciplines.

Anthropology

Anthropology is the disciplined study of human commonalities and differences at the level of groups. Anthropologists describe cultures and societies and analyze how they function, persist, and interact.

The C3 Framework instead justifies anthropology as “centrally concerned with applying their [anthropologists’]research findings to the solution of human problems,” rather than to understanding human beings without seeing them as problems to be solved. The C3 Framework also states that “an engaged anthropology is committed to supporting social change efforts that arise from the interaction between community goals and anthropological research.”13 The C3 Framework also uses anthropology to teach the radical catechism of power and the essential salience of identity groups: “[T]hey ask about the consequences of boundaries within and between societies, including exclusion and differences of power or status, … [C3-ready students] “[u]nderstand the variety of gendered, racialized, or other identities individuals take on over the life course, and identify the social and cultural processes through which those identities are constructed.”14 Anthropology in the Framework also includes instruction in “the global justice movement,” a requirement to “[b]ecome critically aware of ethnocentrism,” and learning to “[a]pply anthropological concepts to current global issues such as migrations across national borders or environmental degradation.”15 The C3 Framework, in other words, yokes anthropology to radical activism, which thinly euphemizes hostility to the American nation, advocacy for illegal immigration, and environmental activism.16

Geography

Geography is the disciplined study of the human relation to the natural and artificial features of the physical landscape, and of the constraints imposed on that relation by the varying availability of resources and technology. Geographical analysis requires study of maps and globes.

The C3 Framework instead redefines geography essentially as an adjunct to “environmental activism”: “Where are people and things located? Why there? What are the consequences? An environmental perspective views people as living in interdependent relationships within diverse environments. … Analyze the effects of catastrophic environmental and technological events on human settlements and migration.”17 The C3 Framework explicitly includes a highly partisan policy recommendation in favor of abrogating American sovereignty: “Global-scale issues and problems cannot be resolved without extensive collaboration among the world’s peoples, nations, and economic organizations.”18

Psychology

Psychology is the disciplined study of the human mind, emphasizing needs, desires, motivations, capacities, emotions, maturation, sensory perception, and personal integration. Psychologists pay attention to both conscious and subconscious states and seek patterns in human variation.

The C3 Framework justifies psychology as a means to understand political issues, “including, but not limited to, those encountered in education, business and industry, and the environment,” and states that a main goal of psychology instruction is to “[a]pply psychological knowledge to civic engagement,” especially with regard to “issues faced by local communities.”19 Such knowledge can be used, for example, to determine whether “individuals have prejudices that affect their perception of ‘who or what is to blame’ for economic crises.”20 The C3 Framework teaches psychology, in other words, as a way to understand communities rather than individuals, to delegitimize political opinion as mental disorder, and to use that disciplinary knowledge in “civic engagement.” There is, of course, nothing less civic than to regard a fellow citizen a priori as a mental patient.

Sociology

Sociology is the disciplined study of human social institutions, including the family, the community, and the nation. It emphasizes analysis of the sources of social order and the causes of social disorder.

The C3 Framework instead justifies sociology as a means to “learn how to effectively participate in a diverse and multicultural society.”21 It also requires students to assent to presuppositions such as the contention that “[g]roup memberships and identities provide or deny certain opportunities and power,” the existence of “social stratification,” and “inequality in obtaining rights and privileges.”22 It presents sociology as requiring “students to examine how they are influenced by their social positions,” rather than to take their beliefs and actions as the result of individual conviction.23 The C3 Framework also states that sociology requires students to “[p]ropose and evaluate alternative responses to inequality” as well as to “propose, plan, and conduct simple research and action projects.”24 The C3 Framework, in other words, uses “sociology” to teach students to understand Americans as a people motivated by group identities structured by stratification and inequality, and to view them as properly the subjects of sociological research and “action projects,” rather than as equal, individual fellow citizens.

All Social Studies Subordinated to Action Civics

From the beginning, the C3 Framework subtly deforms what civic participation is by how it defines both the United States and the nature of “civic engagement.”

IN A CONSTITUTIONAL DEMOCRACY, productive civic engagement requires knowledge of the history, principles, and foundations of our American democracy, and the ability to participate in civic and democratic processes. People demonstrate civic engagement when they address public problems individually and collaboratively and when they maintain, strengthen, and improve communities and societies. Thus, civics is, in part, the study of how people participate in governing society.25

C3 Framework, p. 31.

The C3 Framework fundamentally distorts civics instruction by defining America as a democracy rather than a republic. Civics education that omits America’s republican character omits the fundamental importance of instruction in affection towards and knowledge of our enduring institutions of free government. The C3 Framework then gives priority to “address[ing] public problems.” It only mentions maintaining and strengthening “communities and societies,” and omits what is essential in civics education: maintaining and strengthening our laws, our constitution, and our republic. At the same time, it intrudes the troubling imperative to study the means of “governing society”—when it is precisely the point of a republican government devoted to liberty that society ought to be a realm of self-governance and freedom, and that government ought not to seek to master society. The C3 Framework substitutes loyalty to “democracy,” “community,” and “society” in place of loyalty to the republic, the Constitution, and the law, and imparts an unsettlingly totalitarian impulse to the activity of government.

The C3 Framework then explicitly states that the entire social studies framework is intended as a preparation for action civics—what it euphemizes with phrases such as “consider possible solutions,” “communicate and act upon what they learn,” “informed action,” “practicing the arts and habits of civic life,” and “active and responsible citizenship.”26 The link to what action civics really is, vocational training in community organizing, is hinted more explicitly by the directives to provide instruction in “forming and sustaining groups,” “joining with others to improve society,” and “develop[ing] the capacity to work together to apply knowledge to real problems.”27 What the C3 Framework identifies as the characteristics of Active and Responsible Citizens are the characteristics of community organizers: “ACTIVE AND RESPONSIBLE CITIZENS identify and analyze public problems; deliberate with other people about how to define and address issues; take constructive, collaborative action; reflect on their actions; create and sustain groups; and influence institutions both large and small.”28 Civics generally “enables students not only to study how others participate, but also to practice participating and taking informed action themselves.”29

Throughout, the C3 Framework subordinates civics instructions to “civic engagement.” Character instruction in civic virtues is meant to lead to civic engagement: “students understand virtues and principles by applying and reflecting on them through actual civic engagement—their own and that of other people from the past and present.”30 The C3 Framework instructs students in source evaluation “for the purpose of disciplinary inquiry and civic engagement.”31 The entire Anchor Speaking and Listening Standards 1-6, drawn from the Common Core’s ELA/Literacy Standards, are devoted to “civic engagement”: “When preparing to take informed action, students engage with one another in a productive manner using the skills set forth in the Speaking and Listening Standards.”32

The C3 Framework, moreover, stipulates that civics education is not just a preparation for this “informed action,” but includes this “informed action”: “Civics is not limited to the study of politics and society; it also encompasses participation in classrooms and schools, neighborhoods, groups, and organizations.”33 The C3 Framework requires “civic engagement”—engaged action outside the classroom rather than disengaged study within the classroom—as a component of civics education. This “civic engagement,” moreover, possesses all the attributes of radical community organizing: “Civic engagement in the social studies may take many forms, from making independent and collaborative decisions within the classroom, to starting and leading student organizations within schools, to conducting community-based research and presenting findings to external stakeholders.”34 “Community-based research,” it should be noted, is really “advocacy research” to achieve a policy goal, not the disengaged research which students should be learning in school.

The C3 Framework divides all of social studies instruction into four dimensions of inquiry skills—and one entire dimension, Dimension 4, guides students to take “informed action.”35 This “informed action” is the capstone of Dimension 4: “[T]aking informed action intentionally comes at the end of Dimension 4, as student action should be grounded in and informed by the inquiries initiated and sustained within and among the disciplines. In that way, action is then a purposeful, informed, and reflective experience.”36 Dimension 4’s requirements include the entire range of community organization:

TABLE 30: Suggested K-12 Pathway for College, Career, and Civic Readiness Dimension 4, Taking Informed Action37

| D4.6.K-2. Identify and explain a range of local, regional, and global problems, and some ways in which people are trying to address these problems. | D4.6.3-5. Draw on disciplinary concepts to explain the challenges people have faced and opportunities they have created, in addressing local, regional, and global problems at various times and places. | D4.6.6-8. Draw on multiple disciplinary lenses to analyze how a specific problem can manifest itself at local, regional, and global levels over time, identifying its characteristics and causes, and the challenges and opportunities faced by those trying to address the problem. | D4.6.9-12. Use disciplinary and interdisciplinary lenses to understand the characteristics and causes of local, regional, and global problems; instances of such problems in multiple contexts; and challenges and opportunities faced by those trying to address these problems over time and place. |

| D4.7.K-2. Identify ways to take action to help address local, regional, and global problems. | D4.7.3-5. Explain different strategies and approaches students and others could take in working alone and together to address local, regional, and global problems, and predict possible results of their actions. | D4.7.6-8. Assess their individual and collective capacities to take action to address local, regional, and global problems, taking into account a range of possible levers of power, strategies, and potential outcomes. | D4.7.9-12. Assess options for individual and collective action to address local, regional, and global problems by engaging in self-reflection, strategy identification, and complex causal reasoning. |

| D4.8.K-2. Use listening, consensus-building, and voting procedures to decide on and take action in their classrooms. | D4.8.3-5. Use a range of deliberative and democratic procedures to make decisions about and act on civic problems in their classrooms and schools. | D4.8.6-8. Apply a range of deliberative and democratic procedures to make decisions and take action in their classrooms and schools, and in out-of-school civic contexts. | D4.8.9-12. Apply a range of deliberative and democratic strategies and procedures to make decisions and take action in their classrooms, schools, and out-of-school civic contexts. |

Of these, the key imperative is, “Apply a range of deliberative and democratic strategies and procedures to make decisions and take action in their classrooms, schools, and out-of-school civic contexts.”38 The C3 Framework here explicitly calls for action civics, radical community organizing, as the capstone of Dimension 4, and therefore of their entire social studies curriculum. If this were not enough, the C3 Framework explicitly endorses service-learning: “Opportunities to engage in service-learning experiences also help prepare students for their adult responsibilities in participatory democratic cultures.”39 Finally, “the Inquiry Arc of the C3 Framework culminates in Dimension 4.”40 The entire point of the C3 Framework is to prepare students for action civics.

Conclusion

The C3 Framework substitutes process for content, yokes social studies instruction to the failed Common Core curriculum, politicizes social studies instructions, and subordinates all of social studies instruction to action civics, which replaces civics education with vocational training for left-wing community organizing. No state should adopt the C3 Framework. Any state which has adopted the C3 Framework, or allowed the C3 Framework to shape its social studies standards, should immediately remove these standards and craft new standards. Proper social studies instruction should be content rich, have no connection to the Common Core, and depoliticize social studies instruction. We recommend the Massachusetts History and Social Science Curriculum Framework of 2003 as an excellent model.41

Above all, social studies instruction should focus entirely on academically rigorous classroom instruction and possess no commitments to “action civics,” “service learning,” “civic engagement,” or any other euphemism for vocational training for left-wing community organizing.

Cindy Sharretts contributed extensively to the research and drafting for this Issue Brief. NAS is grateful to her for major contribution.

1 National Council for the Social Studies, et al., College, Career, and Civic Life (C3) Framework for Social Studies State Standards: Guidance for Enhancing the Rigor of K-12 Civics, Economics, Geography, and History (Silver Spring, MD: National Council for the Social Studies, 2013).

2 Stanley Kurtz, “‘Action Civics’ Replaces Citizenship with Partisanship,” The American Mind, January 16, 2021; Thomas K. Lindsay and Lucy Meckler, “Action Civics,”“New Civics,” “Civic Engagement,” and “Project-Based Civics”: Advances in Civic Education? (Texas Public Policy Foundation, 2020); David Randall, Making Citizens: How American Universities Teach Civics(National Association of Scholars, 2017).

3 C3 Framework, pp. 84, 89.

4 Chester E. Finn, Jr., “The failure of civics education—and the Brown Center,” Thomas B. Fordham Institute, July 18, 2018.

5 E. D. Hirsch, Cultural Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know (New York: Vintage Books, 1988).

6 C3 Framework, p. 89.

7 C3 Framework, p. 14.

8 C3 Framework, p. 20, 64. See also p. 50.

9 “Aggregated Growth on NAEP Reading 4th and 8th Grades 2011-2019,” Pioneer Institute https://twitter.com/pioneerboston/status/1222894017509306368. See also Theodor Rebarber, The Common Core Debacle Results from 2019 NAEP and Other Sources (Pioneer Institute White Paper No. 205, April 2020), https://eric.ed.gov/?

10 See also Ralph Ketcham, Anders Lewis and Sandra Stotsky, Imperiling the Republic: The Fate of U.S. History Instruction under Common Core (Pioneer Institute White Paper No. 121, September 2014).

11 C3 Framework, p. 6.

12 C3 Framework, p. 15.

13 C3 Framework, p. 77-78.

14 C3 Framework, p. 79.

15 C3 Framework, p. 79.

16 The Anthropology guidelines, moreover, require students to affirm what is essentially a falsehood, that “[v]ariable physical features like skin color and blood type do not cluster into clear-cut biologically defined races” (C3 Framework,p. 77). This is well-meaning, but largely contradicted by the latest generation of DNA research, which states that “[t]he largest genetic clusters of people correspond to geographic regions and specific populations in Africa, Europe, Asia, Oceania, and the Americas, suggesting that continental-level ancestry captures the greatest population differences in genetic variation.” The same research notes that denying such genetic clustering will worsen medical treatment for different patients suffering from a wide range of diseases: “[W]e contend that the epidemiologic importance of race/ethnicity will never disappear. Genetic research has advanced our understanding of human disease and therapies that, if made available equitably, could advance care and promote health equity in all groups.” Luisa N. Borrell, et al., “Race and Genetic Ancestry in Medicine – A Time for Reckoning with Racism,” The New England Journal of Medicine 384, 5 (2021): pp. 474-480. In South Dakota, for example, students educated by these standards might well kill Native American patients from an ideological refusal to use genomic data to tailor health care to their patients. Future doctors educated by the C3 Framework will be unprepared to treat their patients properly—and all students will be educated to embrace ignorance.

17 C3 Framework, pp. 40, 43.

18 C3 Framework, p. 44.

19 C3 Framework, p. 71-72.

20 C3 Framework, p. 72.

21 C3 Framework, p. 73; and see p. 75.

22 C3 Framework, p. 75; and see p. 76.

23 C3 Framework, p. 73.

24 C3 Framework, p. 75.

25 C3 Framework, p. 31.

26 C3 Framework, pp. 6, 12, 19.

27 C3 Framework, p. 19, 31.

28 C3 Framework, p. 19.

29 C3 Framework, p. 31.

30 C3 Framework, p. 33.

31 C3 Framework, p. 57.

32 C3 Framework, p. 64.

33 C3 Framework, p. 31.

34 C3 Framework, p. 59.

35 C3 Framework, pp. 59-64.

36 C3 Framework, p. 62.

37 C3 Framework, p. 62.

38 C3 Framework, p. 62.

39 C3 Framework, p. 89.

40 C3 Framework, p. 90.

41 Massachusetts Department of Education, Massachusetts History and Social Science Curriculum Framework (2003).